💭 Prelude:

This post marks the beginning of an ongoing collaboration series between

the writer behind ShieldMe and of Critical Consent. Together, we'll be exploring the intersection of technology and politics, along with other engaging topics that we believe will captivate our shared audience. Don't forget to like these posts and subscribe to Robert's channel and to mine to show your support for our shared efforts!Lastly I want to express my gratitude to Robert for his tireless efforts and valuable contributions to this collaboration, this wouldn’t have been possible without his input. I'm truly appreciative of the work & time he put into this post, and I trust you can see that too.

Introduction:

Suddenly seeing political ads about an issue that you deeply care about? Flooded with ads for a certain brand of coffee when you check your feed in the morning? It is quite possible that you are seeing these ads because you have been microtargeted, which is a marketing strategy that uses your personal information to show you certain content on the moments it might be most effective.

With the upcoming US election, as well as elections in Europe and many other parts of the world, it is extremely important for you as a reader and voter to be aware of microtargeting and the effect it may have on your decision-making. Whether that's what brand of coffee to choose or who to vote for, it is important to stay vigilant and be aware of how the information you see might have been influenced by your online behavior, so you can make democratic, informed decisions about everything from spending 9$ on a coffee to choosing your next leader.

Section 1: What is Microtargeting?

Featuring the Cambridge Analytica scandal and other examples of microtargeting

As stated in the introduction, microtargeting is a specific form of marketing. In many ways, it is similar to other forms of marketing that you might be more familiar with. A beer manufacturer would probably rather show its ads during sports events than during a televised sermon. Similarly, you're far less likely to come across a Lego ad during political debates than when watching Spongebob. In fact, an advertiser who wants to reach kids will probably not use TV at all, but advertise through a platform like TikTok or Instagram. That is because advertisers choose when and where to advertise based on who they think their audience is, and where they know this audience spends most of their time. They might only want to show their ads to adults, or to people with a high income, or only to women, in order to ensure they are as effective as possible.

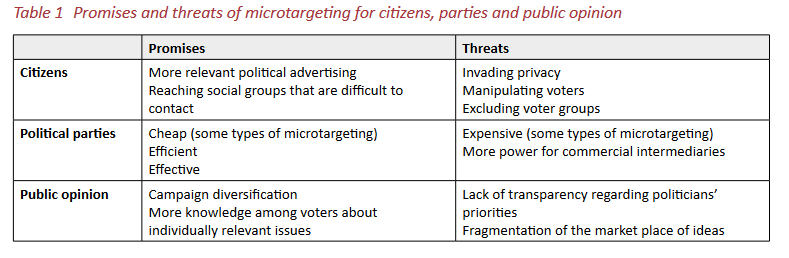

Microtargeting takes this a step further, by using more specific information about you, like political preference, your location and places you visit, products you buy, groups you join, you name it. People can use this information to make certain assumptions about you, and by extension figure out how best to influence you. Some of these assumptions can even seem quite random. Take a look at a sample from a study that used Facebook Likes to predict "highly sensitive personal attributes":

And we are not only talking about ads for products here. These systems are increasingly being used by political campaigns, who can use information about you to target you not only with ads but with content that you are likely to respond to in a certain way. Maybe they use certain language that is more likely to sway you, or maybe they tell you something about their rivals that could dissuade you from supporting them. The information does not even need to be true, it only needs to be persuasive. To best illustrate how this works, let us take a look at one of the most well-known examples of microtargeting, the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Cambridge Analytica was a British data analytics firm that specialized in using personal data from social media platforms, particularly Facebook, to create targeted political advertising campaigns. The scandal erupted when it was revealed that Cambridge Analytica had harvested the personal data of millions of Facebook users, without their knowledge or consent, and used it to influence national elections, including the 2016 U.S. Presidential election and the Brexit referendum in the UK. How much it may have influenced the votes remains unclear.

Cambridge Analytica's microtargeting involved tailoring specific messages and advertisements to very narrow and specific groups of people based on their personal data, to influence their opinions, behavior, and ultimately, their decision-making processes. The firm was able to do this by leveraging the collected data to exploit the unique vulnerabilities, fears, desires, and beliefs of individuals within these specific groups. That way, it effectively made a tailored, emotional appeal that could resonate deeply with the targeted audience. This precision in messaging can increase the likelihood of engagement and, in the context of politics, could influence voters' decisions.

First, Cambridge Analytica gathered data from various sources. It used first-party data from a customer’s own record, such as the use of a supermarket loyalty card, wearable device, social media, and apps, or their activities captured on a website or a mobile phone, including details such as age, gender, location, marital status, political affiliation, hobbies, favorite ice cream flavor etc. It also used second-party data; information collected about a person by another company, such as an online publisher, and sold to others. Furthermore, Cambridge Analytica used third-party data drawn from thousands of sources, comprising demographic, financial, and other data-broker information, including race, ethnicity, and presence of children (O’Hara, 20161; Jeff Chester & Kathryn C. Montgomery, 20172 3).

Next, this data was meticulously analyzed by the firm to reveal patterns and behaviors. All of this information was matched to create highly granular “target audience segments”, where users are categorized into incredibly detailed segmented groups with shared characteristics and interests, such as "young high-income couples who enjoy outdoor activities" or "tech-savvy middle-aged individuals interested in fitness and roller-skating."

Finally, the results were used to create tailored content and advertisements for each segment, resonating with their unique preferences and thus increasing the likelihood of engagement with the advertised message, in this case voting for a specific candidate, as well as to identify and “activate” individuals “across third party ad networks and exchanges”. These Data Management Platforms (DMPs) are quickly becoming a critical tool for political campaigns (Bennett, 20164; Kaye, 2016, July5; Regan, J, 20166).

Section 2: The Evolution of Microtargeting Techniques

From being hit with stones to advertisements, what changed?

The concept of targeting specific demographics and segments has been a part of advertising and political campaigning for decades all around the world. Political microtargeting is not only limited to the English-speaking world. Other countries appear to be copying these techniques. However, early efforts relied on traditional methods like direct mail and phone calls..

The 2000s saw the proliferation of data analytics tools and the collection of vast amounts of personal information, both online and offline. This data was used to refine targeting strategies. Barack Obama's 2008 presidential campaign is often (wrongly) credited with pioneering the use of microtargeting in politics, as its use of Americans' personal data allowed it to target voters with messaging that was specifically tailored to them, by developing voter databases, which included information purchased from commercial data brokerage firms.

A data brokerage firm (also known as a data broker) is a company that collects, processes, and sells consumer information and data to other businesses. These businesses use the data for various purposes, such as marketing, analytics, and decision-making. Data brokers typically gather data from a wide range of sources, including public records, surveys, online activities, and other data points to create highly detailed consumer profiles. Data brokers are everywhere, yet the majority of individuals remain unaware of the existence of major corporations that possess virtually limitless resources, and are solely dedicated to collecting and storing their data. These firms use increasingly complicated and potentially unethical ways to gather data about people without their consent. If you have any kind of public information of the web, a data broker probably has it in their database. The information gathered by these data brokers is then usually sold to marketing agencies, who create segmented marketing databases that store all sorts of personal information about you, like where you live, your ethnicity and marital status, your education and income, things that you buy, what your interests and hobbies are, and what email address(es) and telephone number(s) you use, and try to leverage all of this information in order to persuade you.

The rise of social media platforms, like Facebook, in the mid-2000s created new opportunities for microtargeting. These platforms allowed advertisers and political campaigns to access vast amounts of user data and use it to create highly targeted ad campaigns. Advertisers could now segment their audience based on a variety of criteria, such as age, location, interests, and more. Facebook and Google now play a central role in political operations, offering a full spectrum of commercial digital marketing tools and techniques, along with specialized ad “products” designed for political use (Bond, 2017)7.

It didn't take long for app developers to catch up to the political microtargeting hype. During the 2012 U.S. presidential election, both the Obama and Romney campaigns launched mobile apps, Hillary followed with "Hillary 2016", an app that offers daily challenges and quizzes to Clinton supporters, as well as providing digital and physical rewards to volunteers who help organize and canvas for the Democratic candidate. The "Connect17" app, developed in Germany, shows another way that voter databases can be filled with information, namely by having volunteers go from door to door and entering information about the people they spoke to into a dedicated campaign app. The app rewards door-to-door campaigning, gives points for engaging Facebook posts / SMS messages, and allows a rather clever way of circumventing Germany's strong privacy laws. "Electionear" by Organizer, offers a clear set of instructions and an easy way to collect data about voters, by providing a dynamic script that canvassers can follow in their door-to-door campaigning efforts. The "Footwork" app is another interesting example of the usage of mobile apps in voter canvassing. The application offers canvassers a route-planning tool, designed to streamline their navigation through unfamiliar neighborhoods. Additionally, Footwork offers real-time metrics for individuals managing canvassers to ensure that they effectively cover their assigned areas. Canvassers using the app receive compensation of one cent for each imported voter and one cent for each door they knock on during their campaigns. Just how far these largely unregulated political microtargeting efforts could go to influence voters became clear with the 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal, which for the first time drew widespread attention to microtargeting practices in the context of political campaigns.

Today, politicians and marketers all over the world employ various microtargeting techniques to try to sway people in their favor. Some of these modern techniques include:

Cross-device targeting, which allows marketers to determine if the same person who is on a social network is also using a personal computer and later watching video on a mobile phone.

Programmatic advertising, which employs new automated forms of ad buying and placement on digital media using computer programs and algorithmic processes to find and target a customer no matter where on the web they reside.

Lookalike modelling, which involves starting with a solid group of voters, using that group as an avatar to represent your typical voter or community, and then applying data analysis and machine learning algorithms to this group's data. This information can then be used to target and engage the real community more effectively.

Microtargeting continues to evolve with advancements in data analytics, artificial intelligence, and machine learning. In response to privacy concerns, some regulatory measures have been put in place, such as the European Union's General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) in the United States, which have impacted the way data can be collected and used for microtargeting..

— In the next series of posts, we've got an exciting array of content lined up that promises to inform and intrigue you. We are going to take a look at how effective microtargeting actually is at influencing human behavior, what role the government and social media companies should play in regulating microtargeting, as well as what you can do to protect yourself from being influenced and/or manipulated.

We invite you to join the conversation and share your thoughts, insights, and personal experiences in the comments section. If you find this topic as compelling as we do, we encourage you to help spread the word by sharing this post and our Substacks with your friends, family, and followers. We appreciate your readership; stay tuned for our upcoming posts!

These posts take a lot of effort and research to put together. Show your appreciation to Robert’s hard work and dedication by buying him a coffee, or by getting a paid subscription, which are now 75% off until the end of November!

You can also support my work by subscribing to this publication and pledging a subscription to let me know that you value my content!

O’Hara, C. (2016, January 25). Data triangulation: How second-party data will eat the digital world. Ad Exchanger. Retrieved from http://adexchanger.com/data-driven-thinking/data-triangulation-how-second-party-data-will-eat-the-digital-world/

Chester, J. (2017, January 6). Our next president: Also brought to you by big data and digital advertising. Moyers and Company. Retrieved from http://billmoyers.com/story/our-next-president-also-brought-to-you-by-big-data-and-digital-advertising/

Chester, J., & Montgomery, K. C. (2017, December 31). The role of digital marketing in political campaigns. Center for Digital Democracy, Washington, DC, United States of America; School of Communication. DOI: 10.14763/2017.4.773 Retrieved from http://billmoyers.com/story/our-next-president-also-brought-to-you-by-big-data-and-digital-advertising/

Bennett, C. J. (2016). Voter databases, micro-targeting, and data protection law: Can political parties campaign in Europe as they do in North America? International Data Privacy Law, 6(4), 261-275. DOI:10.1093/idpl/ipw021 Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2776299

Kaye, K. (2016, July 13). Democrats' data platform opens access to smaller campaigns. Advertising Age. Retrieved from http://adage.com/article/campaign-trail/democratic-data-platform-opens-access-smaller-campaigns/304935/

Regan, J. (2016, July 29). Donkeys, elephants, and DMPs. Merkle. Retrieved from https://www.merkleinc.com/blog/donkeys-elephants-and-dmps

Bond, S. (2017, March 14). Google and Facebook build digital ad duopoly. Financial Times. Retrieved from https://www.ft.com/content/30c81d12-08c8-11e7-97d1-5e720a26771b